Four Myths About Investing In India

So, in this section, the author will discuss the four myths about Investing here in India.

MYTH 1: Gold will help me protect my wealth

According to an RBI report, the author found that next to real estate, gold, at 11%, accounts for the largest share of the wealth of Indian households. An 11% allocation to any asset is a reasonably large chunk by any standard. So how has such a material asset allocation worked for Indian households? Over the last ten/twenty/thirty years, the price of gold (in rupee terms) has compounded at an annualized return of 9.2%/12.7%/9.3%, respectively.

Over the same periods, an investment in the equity markets, represented by an investment in the BSE Sensex index, returned 10.4%/15.0%/14.8%, respectively, higher than gold. However, if the author considers returns from gold in each of the three decades separately over the last thirty years, he sees that gold has underperformed the Sensex by a wide margin. In 1990–2000, gold prices grew at an annualized return of just 2.8%, not even beating inflation. The narrowest margin by which gold underperformed was in 2010–2020, when gold prices compounded at 9.2% per annum, against 10.4% of the Sensex. However, in this decade, gold prices were more volatile (measured by the standard deviation) than equities, suggesting that there wasn't a compelling reason to own gold on a volatility-adjusted basis.

Even though gold does not fetch returns superior to equity, it could improve the portfolio's risk-adjusted returns if it were negatively correlated to equities (thus allowing you to diversify your returns). The widespread public perception is that gold is negatively related to equities. However, the data on this is mixed. While gold has been negatively correlated to the Sensex over the past ten years, over more extended periods, namely twenty and thirty years, the negative correlation drops away and becomes a mild positive correlation. This means that the prices of gold and the BSE Sensex have moved more or less in tandem over the last twenty-year and thirty-year periods.

Further, if the author breaks down the last thirty years into three decades, he sees that gold has, for the most period, been positively correlated to equities. This means that using gold as a diversifier of wealth also does not work consistently. On the whole, it is difficult to make a case for gold forming a significant part of the portfolio of an Indian investor.

MYTH 2: Real Estate will help me grow my wealth

Over the last five years, if one were to look at the return rate from real estate in metropolitan cities in India such as Mumbai, Delhi and Bengaluru, one would see that returns have been around 3–4% per annum; i.e., house prices have at best-kept pace with consumer inflation. Real estate in major markets like the National Capital Region has not even accomplished that. However, a school of thought in India says that because residential real estate returns have been weak over the last five years, they will be better going forward. However, this point of view cannot be sustained when one compares Indian house prices with the prices prevalent in other markets. The first problem is affordability. As shown in the chart below, Indian residential house prices, expressed as a proportion of GDP, are 6– 10x the prices prevalent in some comparable Asian economies.

Secondly, Indian residential rental yields are around 2–3% in most Indian cities, whereas the cost of a home loan for prime residential real estate customers is about 7%. The disparity between these numbers suggests that Indian residential real estate still has room to correct from its highs before it becomes an attractive asset class.

Thirdly, comparing Indian residential rental yields with yields in other countries suggests that the Indian residential property market is significantly overvalued. For example, other markets whose rental yields are comparable with India’s—say, Singapore and the USA—have borrowing costs of 2–3%. In contrast, as mentioned above, in India, the price of a home loan for even a prime customer is much higher, around 7%.

The cost of a home loan in India is significantly higher than in Indonesia (7% vs 5%), even though rental yields in Indonesia are much higher than in India. Therefore, investing in real estate in India does not make much economic sense. Add to it other factors—such as high transaction costs (broking, stamp duty, etc.), illiquidity (your property is pretty useless in funding emergency cash calls) and the lack of transparency in finding the actual value or price—and investing in real estate becomes cumbersome and risky.

MYTH 3: Debt mutual funds offer decent returns with low volatility

Salespeople who earn a living by selling mutual funds have popularized the idea that HNIs should invest in debt funds, which give industry-beating returns. Despite the repeated high-profile reverses suffered by prominent mutual fund houses with high-risk, low-quality paper in their debt funds, the intermediary community continues to sell such products. So, why are debt funds far riskier to invest in than many investors believe (and many intermediaries let on)? Personal finance guru Monika Halan has provided an excellent explanation for this:

Remember, when you lend money, the interest is the reward you get for postponing your consumption, taking care of the effects of inflation on the money you get back. The risk of the borrower not returning your money. The government is considered to have no risk of default, and therefore the rate at which the government borrows is called the risk-free rate. As the creditworthiness of firms falls, the interest they offer rises. When you invest in a debt fund, the scheme buys bonds and other fixed return instruments. The risk in debt funds comes from several sources. The author will discuss the three most important aspects of this conversation.

The first is interest rate changes, or an interest rate risk. This is the risk of your fund manager’s interest rate call going wrong.

The second is the risk of default by the borrower—or credit risk. Funds can invest in debt papers rated investment grade by credit rating agencies. But within this band of investment-grade, fund houses can invest in lower-rated papers than the safest paper in the market. As a result, when things go wrong for the firm that borrowed money from the mutual fund, the credit ratings can drop sharply, and the fund's value suffers. When such an event happens, there is a significant redemption pressure.

The third risk kicks in lack of liquidity—or the lack of a market when you want to exit.

The non-government Indian bond market is not very liquid; that is, fund managers may not find buyers if they need to sell in distress.

A debt mutual fund’s return is a function of:

1) Yield to Maturity or YTM,

2) Mark to Market or MTM,

3) Expense Ratio.

Let’s delve into these: MTM and the expense ratio should not differ markedly between debt mutual funds. That brings us to the YTM, which refers to the total return earned on a bond held until maturity with interest reinvested at the same rate. The YTM of a debt fund is the weighted average yield of all its investments. The yield of a debt fund depends on the credit quality of its portfolio.

All corporate debts are ‘rated’ based on the probability of the corporation defaulting on its debt obligations. These ratings are provided by credit rating agencies that, the world over, are conflicted because the issuer of the debt pays the credit rating agency its fees. The debt issuers with the strongest balance sheets get a rating of ‘AAA’, implying that their probability of default is similar to that of the government.

In contrast, companies with poor debt management may get a rating of ‘B’.

There tends to be an inverse correlation between the rating enjoyed by the debt issuer and the YTM on the issuer’s bonds, i.e., companies with the strongest ratings enjoy the lowest YTMs. That, in turn, means that a fund manager who stuffs his debt fund full of highly-rated bonds will have a fund with a low YTM, and hence the debt fund will give low returns. However, that will make the fund unpopular with the army of salespeople who sell such products. So, fund managers who want to earn significant bonuses tend to stuff their debt funds full of bonds with low credit ratings.

Such funds deliver high returns for a few years, but when defaults occur (low-rated bonds have high default risk), the whole thing blows up, and millions of investors find that their savings in debt funds are worth much less than they thought they would be.

MYTH 4: GDP growth drives the stock market. So, if I can time the economic cycle, I can time the stock market

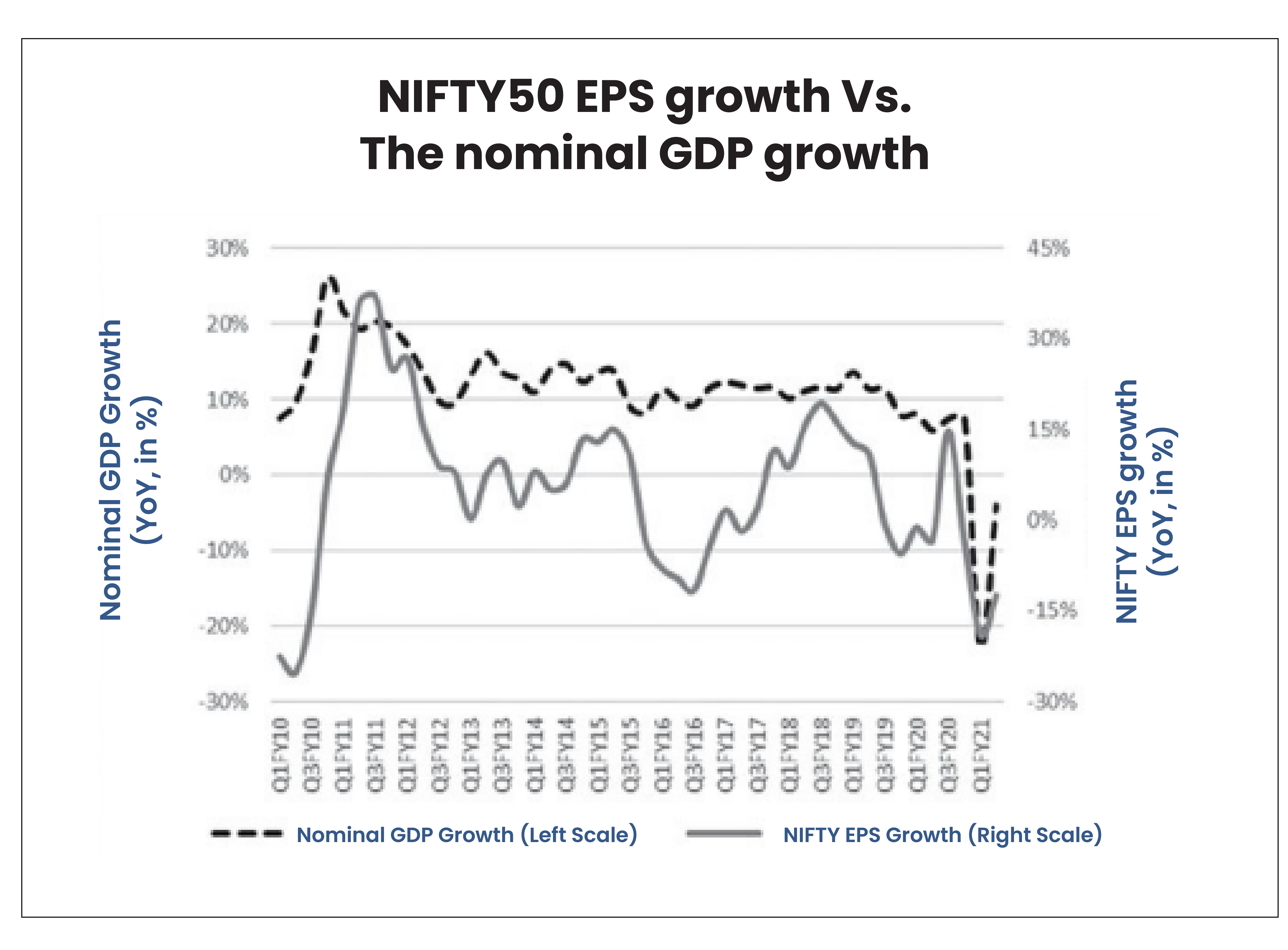

In a blog post published by Marcellus in November 2019, they have shown that the relationship between Nifty50 EPS growth and GDP growth seems to have completely broken down in the last five years.

Do note two things in the chart above:

(1) the growing gap between the two lines;

(2) the fact that the lines often go in opposite directions.

To understand why the Nifty50 no longer captures the dynamism of the Indian economy, an excellent place to start is the index as it stood ten years ago. The ten-year (2011–2020) share price return from investing in the Nifty50 is 9% (on a total return basis), i.e., significantly lower than India’s nominal GDP growth, which, over the same decade, has been around 12% per annum.

More generally, there tends to be low or no correlation between stock markets and GDP growth across the world, implying that timing the stock market is not possible on a systematic basis. For example, Ben Inker of the fund management house GMO, in an article in 2012, concluded that ‘Stock market returns do not require a particular level of GDP growth, nor does a particular level of GDP growth imply anything about stock market returns.’

The valuation guru Aswath Damodaran says that instead of running from GDP growth to the stock market, the causal relationship runs the other way round, i.e., stock markets are predictors of GDP growth (rather than being ‘reflectors of GDP growth’). So, for example, he highlights a 30% correlation between stock market returns in the US in the period 1961–2019 and GDP growth four quarters hence.

Reality: Equities are a better way to build wealth

Suppose gold, real estate, bank deposits and corporate debt (through mutual funds) do not optimally balance risk, returns, diversification and financial objectives for Indian savers. What other options do they have to invest in and build their wealth? Are equities the answer? Let’s find out in the next section.